Don't let perfect be the enemy of good

Another two weeks have flown by so quickly! Actually, I have been terribly sick these past two weeks, because I jinxed myself by bragging that I haven't been sick since October. But, I am recovering well and finally able to blog again (thanks to everyone who pushed me! So grateful y'all are reading!)

We have (mostly) finished our rotations through the different clinics. With the current nurses' strike, public hospitals are operating at sub-optimal levels, which has led to changes in our schedules. But, my focus now is working on my research project, a diagnostic mobile x-ray truck that operates in the most rural areas of Busia County. The truck was a response to the spread of TB in Kenya, which goes undetected and kills many people, especially in areas of close proximity. I have been traveling out to these clinics (about 3 hours away from where we are) with Joe Mamlin (undoubtedly something I will treasure forever and ever) to talk to the clinicians and ask them about the challenges they face in utilizing the truck services. Everyone has such great perspective and honest feedback. The operation of the truck really reflects many challenges rural medicine faces, including basics like lack of functioning computers to access the XR images or Internet. I approached this project quite timidly (after all, who is this kid asking questions of these amazing clinicians who do SO much to help their patients?), but I have found that everyone is so willing to talk to me, and it seems, really happy that their perspective is being solicited and valued. This is something Joe has mentioned too-he travels out to these clinics every week "for 12 different reasons", one of which is to go out and get a feel for how everything is actually running, something you cannot gauge from three hours away. He wants to make sure the clinicians out in these rural areas feel supported and I am continually amazed by his genuine, personal connections with both patients and clinicians.

Me with Joe at Lake Victoria-already one of my favorite pictures

I have been reading, too! I just finished the book Mountains Beyond Mountains, a biography about Dr. Paul Farmer. Dr. Farmer is regarded as a pioneer in global health and has worked in Haiti, Peru, and Russia to provide healthcare in rural areas, to those who otherwise do not have access. I think this book really helped me continue thinking about how I fit into a global health landscape, especially why me, why now, and why here. My blog post title is inspired by a quote in the book-one that I've heard before, but that really resonated with me this time. Of course, undergraduates and fledgling medical students are not fully licensed physicians with a developed skill set, but exposing students when they are young, and giving them the opportunity to learn and grow from their mentors is how the next generation of global health leaders will be shaped. Arguably, this is good, and makes sure the work keeps getting done. So, if I'm here, and if I don't come back to work in global health, are these opportunities and resources wasted on me? I posed this question to my wonderful, thoughtful friend Ashley over Facetime and she assuaged me much more concisely and beautifully than I will put it now-that my time here, even if it doesn't manifest into me coming back to this exact organization to work, that I will still pay it forward in many way, by telling others about my experience, in my interactions with my future patients, and in ways I have yet to imagine. In a perfect world, the most qualified people would be here, doing this work. Actually, in a perfect world, every healthcare system would be fully developed and independently functioning within their own communities. But, it is important to remember thatgood,maybe not perfect, butgood, work is done by individuals who want to make a difference, bring others into their vision, and build together.

My good friend Aparna, who is also doing wonderful public health work in HIV/AIDS in NYC, wants to hear more about the HIV resistance clinic here, so I will take a second to talk about that now. Yes, HIV resistance! I did not know HIV could be resistant until I got here, either. Here, after a patient is diagnosed with HIV, they are started on first-line antiretroviral drugs, which I have been told are "fairly easy to mess up." After six months of treatment, their viral loads are measured and their adherence is assessed. If a patient fails first-line treatment, they are started on second-line ARTs, which have more side effects and are typically taken twice a day. If a patient is failing second-line treatment, here is where HIV resistance clinics come in. 90% of the time, patients are failing treatment because of adherence issues-stigma against taking the medicine, side effects from medication, or just a lack of desire to take the medicine. The other 10% of the time, the HIV strain the patient has does have resistance against the ARTs. However, it is hard to have genotype services performed here, so clinicians look for the typical presentation associated with resistance, the major giveaway being that the patient's viral loads are usually consistent around a 1000-2000 copies/mL. So, more than in any clinic I have seen, HIV resistance clinicians spend time assessing a patient's motivations in taking medicine, home life, stress levels, access to food, and more, because most patients are not resistant to the virus they have.

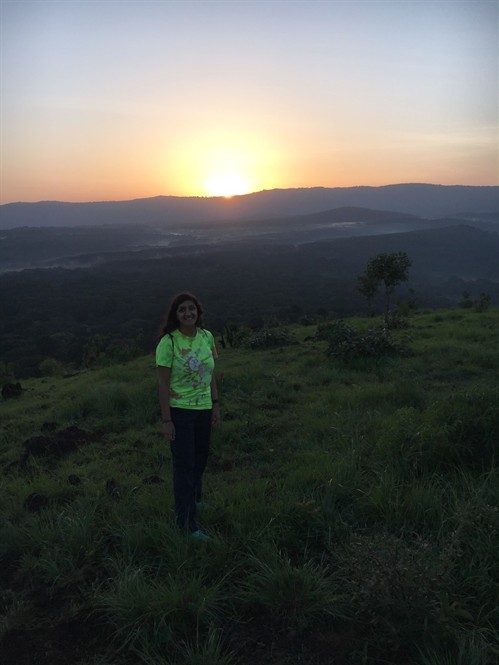

Travel! Two weekends ago, I went to Kakamega Rainforest with a small group of people. We stayed at a resort in the middle of the forest, which was so relaxing and wonderful. We took two hikes, one of which was a hike at 5 AM up a mountain to see a sunrise. It was beautiful--I almost wish I woke up more often to see sunrises--almost.

Sunrise hike at Kakamega Rainforest